Indus Valley Civilization Arts

- The arts of the Indus Valley Civilisation emerged during the second half of the third millennium BCE. The forms of art found from various sites of the civilisation include sculptures, seals, pottery, jewellery, terracotta figures, etc.

- The artists of that time surely had fine artistic sensibilities and a vivid imagination. Their delineation of human and animal figures was highly realistic in nature, since the anatomical details included in them were unique, and, in the case of terracotta art, the modelling of animal figures was done in an extremely careful manner.

Sculptures:

- Statues whether in stone, bronze or terracotta found in Harappan sites are not abundant, but refined.

- The stone statutes found at Harappa and Mohenjodaro are excellent examples of handling three-dimensional volumes.

- In stone are two male figure are extensively discussed: one is a torso in red sandstone and the other is a bust of a bearded man in soapstone.

- Male torso:

-

-

- There are socket holes in the neck and shoulders for the attachment of head and arms. The frontal posture of the torso has been consciously adopted.

- The shoulders are well baked and the abdomen slightly prominent.

- The figure of the bearded man:

-

So called “Priest-King” in Mohenjodaro made of soapstone - It has been interpreted as a priest, is draped in a shawl coming under the right arm and covering the left shoulder.

- This shawl is decorated with trefoil patterns.

- The eyes are a little elongated, and half-closed as in meditative concentration.

- The nose is well formed and of medium size;

- The mouth is of average size with close-cut moustache and a short beard and whiskers;

- The ears resemble double shells with a hole in the middle.

- The hair is parted in the middle, and a plain woven fillet is passed round the head.

- An armlet is worn on the right hand and holes around the neck suggest a necklace.

-

- Others:

- A seated stone ibex or ram (49 × 27 × 21 cm) at Mohenjodaro.

- A stone lizard at Dholavira.

- The only large piece of sculpture is that of a broken, seated male figure from Dholavira.

-

- Bronze Casting:

- The art of bronze-casting was practised on a wide scale by the Harappans. Their bronze statues were made using the ‘lost wax’ technique in which the wax figures were first covered with a coating of clay and allowed to dry.

- Then the wax was heated and the molten wax was drained out through a tiny hole made in the clay cover.

- The hollow mould thus created was filled with molten metal which took the original shape of the object. Once the metal cooled, the clay cover was completely removed.

- In bronze we find human as well as animal figures:

- The best example of the former being the statue of a girl popularly titled ‘Dancing Girl’.

A bronze statuette dating around 2500 BC “dancing girl of Mohenjo Daro.

A bronze statuette dating around 2500 BC “dancing girl of Mohenjo Daro.

- Dancing One of the best known artefacts from the Indus Valley is this approximately four-inch-high figure of a dancing girl.

- Found in Mohenjodaro, this exquisite casting depicts a girl whose long hair is tied in a bun. Bangles cover her left arm, a bracelet and an amulet or bangle adorn her right arm, and a cowry shell necklace is seen around her neck.

- Her right hand is on her hip and her left hand is clasped in a traditional Indian dance gesture.

- She has large eyes and flat nose. This figure is full of expression and bodily vigour and conveys a lot of information.

- Amongst animal figures in bronze the buffalo with its uplifted head, back and sweeping horns and the goat are of artistic merit.

This bronze figure of a bull from Mohenjodaro deserves mention. The massiveness of the bull and the fury of the charge are eloquently expressed. The animal is shown standing with his head turned to the right and with a cord around the neck

- The best example of the former being the statue of a girl popularly titled ‘Dancing Girl’.

- Bronze casting was popular at all the major centres of the Indus Valley Civilisation. The copper dog and bird of Lothal and the bronze figure of a bull from Kalibangan are in no way inferior to the human figures of copper and bronze from Harappa and Mohenjodaro.

- Metalcasting appears to be a continuous tradition. The late Harappan and Chalcolithic sites like Daimabad in Maharashtra yielded excellent examples of metal-cast sculptures. They mainly consist of human and animal figures. It shows how the tradition of figure sculpture continued down the ages.

- Same techniques are practised even now in many parts of the country.

- The art of bronze-casting was practised on a wide scale by the Harappans. Their bronze statues were made using the ‘lost wax’ technique in which the wax figures were first covered with a coating of clay and allowed to dry.

- Terracotta:

-

Toy Cart

Terracotta Figures - The Indus Valley people made terracotta images also but compared to the stone and bronze statues the terracotta representations of human form are crude in the Indus Valley. They are more realistic in Gujarat sites and Kalibangan.

- The most important among the Indus figures are those representing the mother goddess. Although such worship of female deities reflects the ability to visualize divinity in feminine form, it does not necessarily translate into power or a high social position for ordinary women.

-

Mother goddess, terracotta -

A terracotta figurine

-

- In terracotta, we also find a few figurines of bearded males with coiled hair, their posture rigidly upright, legs slightly apart, and the arms parallel to the sides of the body. The repetition of this figure in exactly the same position would suggest that he was a deity.

- A terracotta mask of a horned deity has also been found.

- Toy carts with wheels, whistles, rattles, birds and animals, gamesmen and discs were also rendered in terracotta.

- Clay marbles have been found in courtyards of houses.

- There are figurines of children playing with toys.

- Lots of terracotta figurines of dogs have been found at Harappan sites, some with collars, suggesting that people kept dogs as pets.

- The Harappan craftspersons also made terracotta bangles.

- Making of hard, high-fired bangles known as stone ware bangles.

- These were highly burnished red or grey-black and usually had tiny letters written on them.

- Terracotta figurines of women at work are few.

- Figurines depicting women grinding or kneading something have been found at Nausharo, Harappa, and Mohenjodaro, suggesting the association of women with food-processing activities.

- Some of the fat female terracotta figurines may represent pregnant women.

-

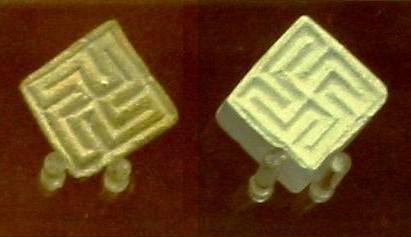

Seals:

- Archaeologists have discovered thousands of seals, mostly made of steatite, and occasionally of agate, chert, copper, faience and terracotta, with beautiful figures of animals, such as unicorn bull, rhinoceros, tiger, elephant, bison, goat, buffalo, etc. The realistic rendering of these animals in various moods is remarkable.

- The purpose of producing seals was mainly commercial. It appears that the seals were also used as amulets, carried on the persons of their owners, perhaps as modern-day identity cards.

- The standard Harappan seal was a square plaque 2×2 square inches, made from steatite.

- Every seal is engraved in a pictographic script which is yet to be deciphered.

- Some seals have also been found in ivory. They all bear a great variety of motifs, most often of animals including those of the bull, with or without the hump, the elephant, tiger, goat and also monsters. Sometimes trees or human figures were also depicted.

- The most remarkable seal is the one depicted with a figure in the centre and animals around. This seal is generally identified as the Pashupati Seal by some scholars whereas some identify it as the female deity.

Pashupati Seal - This seal depicts a human figure seated cross-legged.

- An elephant and a tiger are depicted to the right side of the seated figure, while on the left a rhinoceros and a buffalo are seen.

- In addition to these animals two antelopes are shown below the seat.

- Seals such as these date from between 2500 and 1900 BCE and were found in considerable numbers in sites such as the ancient city of Mohenjodaro in the Indus Valley. Figures and animals are carved in intaglio on their surfaces.

- Square or rectangular copper tablets, with an animal or a human figure on one side and an inscription on the other, or an inscription on both sides have also been found.

- The figures and signs are carefully cut with a burin. These copper tablets appear to have been amulets.

- Unlike inscriptions on seals which vary in each case, inscriptions on the copper tablets seem to be associated with the animals portrayed on them.

Pottery:

- A large quantity of pottery excavated from the sites, enable us to understand the gradual evolution of various design motifs as employed in different shapes, and styles. The Indus Valley pottery consists chiefly of very fine wheelmade wares, very few being hand-made.

- Plain pottery is more common than painted ware. Plain pottery is generally of red clay, with or without a fine red or grey slip. It includes knobbed ware, ornamented with rows of knobs. The black painted ware has a fine coating of red slip on which geometric and animal designs are executed in glossy black paint.

- Painted Earthen Jar of Mohenjodaro: This jar is made on a potter’s wheel with clay. The shape was manipulated by the pressure of the crafty fingers of the potter. After baking the clay model, it was painted with black colour. High polishing was done as a finishing touch. The motifs are of vegetals and geometric forms. Designs are simple but with a tendency towards abstraction.

- There is a great variety of pottery, including black-on-red, grey, buff, and black-and-red wares.

- At the earliest levels of Mohenjodaro, a burnished grey ware with a dark purplish slip and vitreous glaze may represent one of the earliest examples of glazing in the world.

- Polychrome pottery is rare and mainly comprises small vases decorated with geometric patterns in red, black, and green, rarely white and yellow.

- Incised ware is also rare and the incised decoration was confined to the bases of the pans, always inside and to the dishes of offering stands.

- Perforated pottery includes a large hole at the bottom and small holes all over the wall, and was probably used for straining beverages.

- Pottery for household purposes is found in as many shapes and sizes as could be conceived of for daily practical use. Straight and angular shapes are an exception, while graceful curves are the rule.

- Miniature vessels, mostly less than half an inch in height are, particularly, so marvellously crafted as to evoke admiration.

- The functions of the Harappan pots:

- The large jars may have been used to store grain or water.

- The more elaborately painted pots may have had a ceremonial use or may have belonged to rich people.

- Small vessels may have been used as glasses to drink water or other beverages.

- The function of the perforated jars:

- One suggestion is that they may have been wrapped in cloth and used for brewing fermented alcoholic beverages.

- Another possibility is that they may have had a ceremonial or ritualistic use.

- Shallow bowls probably held cooked food; flattish dishes were used as plates.

- Cooking pots of various sizes have been found.

- Most of them have a red- or black-slipped rim and a rounded bottom.

- The rims of the cooking pots are strong and project outwards to help pick them up or move them around.

- Some of the forms and features of the pots used by the Harappans can be seen in traditional kitchens even today.

Beads and Ornaments:

- The Harappan men and women decorated themselves with a large variety of ornaments produced from every conceivable material ranging from precious metals and gemstones to bone and baked clay.

- While necklaces, fillets, armlets and finger-rings were commonly worn by both sexes, women wore girdles, earrings and anklets.

- Hoards of jewellery found at Mohenjodaro and Lothal include necklaces of gold and semi-precious stones, copper bracelets and beads, gold earrings and head ornaments, faience pendants and buttons, and beads of steatite and gemstones. All ornaments are well crafted.

- A hoard of jewellery made of gold, silver, and semi-precious stones was found also at the small village site of Allahdino.

- A touchstone bearing gold streaks was found in Banawali, which was probably used for testing the purity of gold.

- It may be noted that a cemetery has been found at Farmana in Haryana where dead bodies were buried with ornaments.

- There is some degree of overlap in male and female hairstyles and ornaments, but also some differences.

- For instance, men and women both wear bangles and necklaces, but men rarely wear multi-strand necklaces made of graduated beads.

- The bead industry seems to have been well developed as evident from the factories discovered at Chanhudaro and Lothal.

- Beads were made of carnelian, amethyst, jasper, crystal, quartz, steatite, turquoise, lapis lazuli, etc. Metals like copper, bronze and gold, and shell, faience and terracotta or burnt clay were also used for manufacturing beads.

- The beads are in varying shapes—disc-shaped, cylindrical, spherical, barrel-shaped, and segmented. Some beads were made of two or more stones cemented together, some of stone with gold covers. Some were decorated by incising or painting and some had designs etched onto them. Great technical skill has been displayed in the manufacture of these beads.

- The Harappan people also made brilliantly naturalistic models of animals, especially monkeys and squirrels, used as pin-heads and beads.

- Bead making was a craft known in earlier cultures, but in the Harappan civilization new materials, styles, and techniques came into vogue.

- A new type of cylindrical stone drill was devised and used to perforate beads of semi-precious stones. Such drills have been found at sites such as Mohenjodaro, Harappa, Chanhudaro, and Dholavira.

- The Harappan long barrel cylinder beads made out of carnelian were so beautiful and valued that they found their way into royal burials in Mesopotamia.

- The barrel shaped beads with trefoil pattern are typically associated with the Harappan culture.

- Tiny micro-beads were made of steatite paste and hardened by heating. Beads were also made of faience.

Clothes:

- Women:

- Going by the figurines, Harappan women wore a short skirt made of cotton or wool.

- Men:

- Male figurines are usually bare headed, though some are turbaned. Most of them are nude, so it is difficult to say what sort of clothes men wore.

- Certain stone sculptures suggest the use of a dhoti-like lower garment and an upper garment consisting of a shawl or cloak worn over the left shoulder and under the right arm.

- The other dress was a kilt and a shirt worn by both men and women.

- They used cotton clothes also that in one sculpture the cloth was shown as having trefoil pattern and red colours.

- It is evident from the discovery of a large number of spindles and spindle whorls in the houses of the Indus Valley that spinning of cotton and wool was very common. Spinning is indicated by finds of whorls made of the expensive faience as also of the cheap pottery and shell.

- Men and women wore two separate pieces of attire similar to the dhoti and shawl. The shawl covered the left shoulder passing below the right shoulder.

Consciousness of fashion Hairstyle:

- From archaeological finds it appears that the people of the Indus Valley were conscious of fashion. Different hairstyles were in vogue and wearing of a beard was popular among all.

- Cinnabar was used as a cosmetic and facepaint, lipstick and collyrium (eyeliner) were also known to them.

- Women:

- They wore their hair variously in braids, rolled into a bun at the back or side of the head, arranged in separate locks or ringlets, and wrapped around the head like a turban.

- What looks like a fan-shaped headdress could actually represent hair stretched over a frame made of bamboo or some other material.

- At Harappa, it is supplemented by flowers or flower-shaped ornaments. Such hairstyles or headdresses could indicate women of distinction or deities.

- Men:

- There are various hairstyles—braids, buns, and hair hanging loose.

- Most of the male figurines have beards, in styles ranging from the ‘goatee’ to the more common combed and spreadout style as in the case of the ‘priest-king’.

- Men and women alike had long hair.

Decorations:

- The painted decorations consist of horizontal lines of varied thickness, leaf patterns, scales, chequers, lattice work, palm and pipal trees.

- The decorative patterns range from simple horizontal lines to geometric patterns and pictorial motifs.

- Geometrical patterns, circles, squares and triangles and figures of animals, birds, snakes or fish are frequent motifs found in Harappan pottery.

- Animals depicted are humped bulls, pumas, birds, etc. Bulls and pumas symbolized abundance, fecundity and power.

- Sometimes they are also depicted facing a tree in a scene that may be interpreted as receiving life from a sacred tree of life.

- Another favourite motive was tree pattern. Plants, trees and pipal leaves are found on pottery.

- A jar found at Lothal depicts a scene in which two birds are seen perched on a tree each holding a fish in its beak.

- Human figures are rare and crude.

- Some of the designs such as fish scales, palm and pipal leaves, and intersecting circles have their roots in the early Harappan phase.

Shell work:

- Beads, bracelets, and decorative inlay work of shell show the existence of craftspersons skilled in shell working.

- Bangles were often made from conch shell.

- Chanhudaro and Balakot were important centres of shell work.

- Further evidence of site specialization comes from Gujarat.

- Excavations at Nageshwar (in Jamnagar district) have shown that this site was exclusively devoted to shell-working and specialized in making bangles.

- Evidence of shell working also comes from Kuntasi, Dholavira, Rangpur, Lothal, Nagwada, and Bagasra.

- This craft was clearly very important in the Gujarat region of the Harappan culture zone.

Others:

- Impressions on clay floors and fired clay lumps suggest traditions of making baskets and mats out of reeds and grasses.

- A number of gold, terracotta and stone figurines of girls in dancing poses reveal the presence of some dance form.

- Some make-up and toiletry items (a special kind of combs, the use of collyrium and a special three-in-one toiletry gadget) that were found in Harappan contexts still have similar counterparts in modern India.

- A harp-like instrument depicted on an Indus seal and two shell objects found at Lothal indicate the use of stringed musical instruments.

- The Harappans also made various toys and games, among them cubical dice (with one to six holes on the faces), which were found in sites like Mohenjo-Daro.

- The people of the Indus Valley Civilization, from the early Harappan periods, had knowledge of proto-dentistry. Evidence for the drilling of human teeth in vivo (i.e., in a living person) was found in Mehrgarh.

Criticism of Harappan artworks:

- The artworks of the Harappans leave us a little disappointed on two counts:

-

- The finds are very limited in number and

- they do not seem to have the variety of expression seen in the contemporary Civilizations of Egypt and Mesopotamia.

- Stone sculptures was rare and undeveloped compared to those fashioned by the Egyptians.

- The terracotta pieces also cannot compare with those of Mesopotamia in quality.

- It is possible that the Harappans were using less durable medium like textile designs and paintings for their artistic expression, which have not survived.

-